Greta Garbo

Greta Garbo

Greta Garbo

Scott Lord on the Silent Film of Greta Garbo, Mauritz Stiller, Victor Sjostrom as Victor Seastrom, John Brunius, Gustaf Molander - the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film........Lost Films in Found Magazines, among them Victor Seastrom directing John Gilbert and Lon Chaney, the printed word offering clues to deteriorated celluloid, extratextual discourse illustrating how novels were adapted to the screen; the photoplay as a literature;how it was reviewed, audience reception perhaps actor to actor.

Saturday, December 31, 2022

The Photoplay: Silent Film Lobby Card

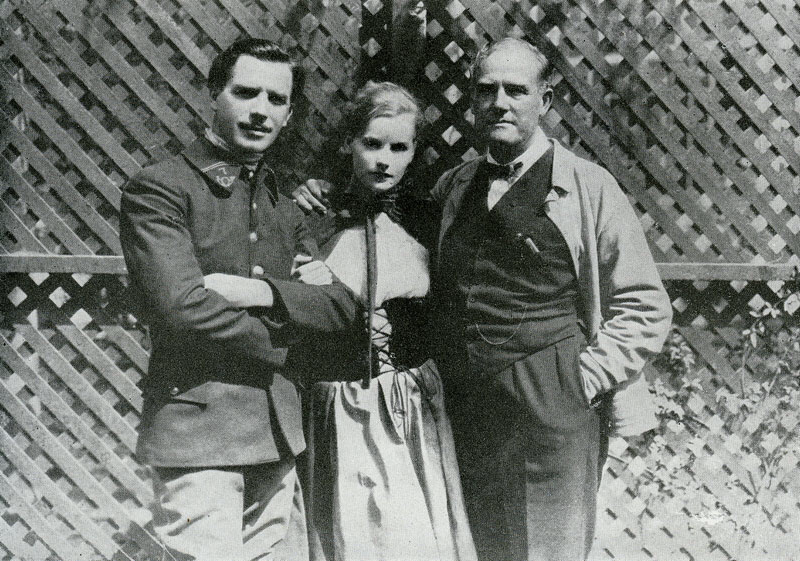

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

9:06:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Greta Garbo,

Greta Garbo Category Film Actress,

Greta Garbo Film Actress,

Greta Garbo in the Single Standard,

Greta Garbo in The Temptress

Sherlock Holmes The Man With The Twisted Lip (Maurice Elvey, 1922)

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

6:44:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Silent Film,

Silent Film Scott Lord

Greta Garbo Magazine Cover

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

5:37:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Garbo,

Greta Garbo,

Greta Garbo Extratextual Discourse,

Scott Lord Silent Film

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

The Silent Film of Alfred Hitchcock

"I first started in 1920...There was a scenario department so you had a scenario editor and his assistant. My job at the time was designing the titles, because titles because titles were very important since whole stories could be changed, characters could be changed merely by the wording inthe title. I was then given odd jobs of going out to shoot odd litlle entrances and exits on exteriors. So gradually I practiced my hand at scriptwriting myself. I took any story and after the script was written it was handed to the director."

Alfred Hitchcock (quoted by Eric Sherman)

The Kinematograph Yearbook of 1928 include with the screen credits then acquired by Alfred Hitchcock those of his having been assistant and scenarist to director Graham Cutts on the films "Woman to Woman", "Blackguard" and "Passionate Adventure". The periodical credits Hitchcock as the director of "Pleasure Garden" (1926) after his joining Gainsborough Pictures in 1925. During filmed interviews late in his career, Hitchcock reflects that he had been trained in American silent film, despite the studios having been located in England- that the influence of Murnau and Eisenstien had only been subsequent.

Interestingly, in his recent academic paper Silent Hitchcock, author Robert Murphy, instructor at De Montfort University, Leicester, asks how important a silent film director Alfred Hitchcock was by wondering if Hitchcock had been killed with F.W. Murnau, that is if he had only made silent film and ended with Blackmail, which would have been his tenth silent, would his films still be studied or overlooked. Oddly, the author has chosen Hitchcock, who in fact often repeated camera set ups in his American sound films that he had previously used in lower budget British silent films, returning to redo elements of scenes and motifs he had used earlier- an ostensible reason for this being that he collaborated as a director on scripts with his wife both in England and in the United States which may have brought a sentimentality when the production costs of his films were much larger.

Murphy, in Silent Hitchcock, surveys Hitchcock's silent career, beginning by noting that "The Mountain Eagle" (1926) is a lost film. "All that survives of 'The Mountain Eagle' are the six stills reproduced in Truffaut's book of interviews with Hitchcock and we have no way of knowing if the film was as terrible as Hitchcock thought it was." It was in fact based on an original script rather than a popular novel or stage vehicle. The film stars actress Nita Naldi.

What miraculously does survive is one of the silent films to which Alfred Hitchock wrote the Photoplay, "White Shadow", directed in 1924 by Graham Cutts. Once thought to have been lost, the film is now restored and considered incomplete, the first three reels having been discovered in New Zealand during 2010, The film, adapted by Hitchcock from a novel by Michael Morton, stars actress Betty Compson in a dual role of good and bad twin sisters. The film was originall released with a length of six reels and was co-scripted and edited by Alma Reville. As a director, Cutts has been noted by critics for his compositions in the film, particularly for the use of backlighting during night interiors.

The British Film Institute presently lists "Woman to Woman" directed by Graham Cutts a year earlier in 1923 as being "lost", there being no known surviving copies held in archives around the world and no ongoing prints that are currently being restored. Eight reels in length, it was written by Alfred Hitchock, the assistant director to the film, and edited by Alma Reville, the two apparently having first met during its filming in some accounts. Betty Compson stars in the film.

More likely Hitchcock had known Alma Reville, if only slightly, during 1922 while an intertitle writer for the film "The Man From Home" directed by George Fitzmaurice and written by Ouida Bergee, who later married the actor Basil Rathbone. Alma Reville edited the film which had not been seen untill only recently when a copy was found in The Netherlands and untill then having had been presumed lost. George Fitzmaurice also that year directed the film "Three Live Ghosts", written by Ouida Bergere.

The existing print, and untranslated copy of the film "The Man from Home" was discovered by authors Alain Kerzoncof and Charles Barr, who in their book Hitchcock Lost and Found note that Hitchcok telephoned Alma Reville later when an assistant director.

Alfred Hitchcock also scripted the film "Dangerous Virtue", directed by Graham Cutts during 1925 in Islington, London. The film stars actresses Jane Novak and Julliane Johnstone. Hitchcock is credited as assistant director and Betty Compson appears in the film in a smaller than before role and Miles Mander appears in the film. Motion Picture News Booking Guide of 1926 provided a brief synopsis, "Society melodrama based on eternal triangle. Philandering Frenchman captures American girl's heart. She is too much of a prude for him, however, and he becomes infatuated with Russian, who dies. Spirit of vengeance in Frenchman's heart towards American girl is eventually supplanted by love." The film is more commonly known by the title "The Prude's Fall" and exists in the form of an incomplete print- although three reels survive, the beginning of the film is missing.

Director Graham Cutts was followed by the press in more than two sundry accounts; Kinematograph Yearbook of 1928 reported that to end 1926, " Graham Cutts turned down an invitation to name his own price to direct a picture for an American firm." It added that during the following month he had severed his affiliation with Piccadilly Pictures.

---Director Graham Cutts was followed by the press in more than two sundry accounts; Kinematograph Yearbook of 1928 reported that to end 1926, " Graham Cutts turned down an invitation to name his own price to direct a picture for an American firm." It added that during the following month he had severed his affiliation with Piccadilly Pictures.

Film restoration attempts noticed the stylistic difference between the intertiles used during the films of Alfred Hitchcock by the two companies Gainsborough and British International, Gainsborough aiming at a more literary, artistic, perhaps old-fashioned feel of exposition, with British International veering more towards the reportage of dialogue within the narrative. Scholar Robert Murphy sees a more extensive use of location shooting when Hitchcock left Gainsborough studios for British international Pictures, and indeed, Hitchcock would continue to incorporate famous outdoor settings during climatic scenes, frequently as a backdrop for the McGuffin throughout his entire career, but while assessing Hitchcock s a silent director,he adds, "If Hitchcock makes use of outdoor realism, he by no means abandons Expressionism, though there's a refining down into something more akin to subjective Impressionism." Robert Murphy concludes with an anti-climatic tone, not realizing that it is the auteur of Hitchcock's technique that compels the audience to find the Hitchcockian theme of suspense and disclosure in his object motifs, "His Gainsborough films show a young director constantly subjecting the medium to a barrage of experiments."

When I wrote to Professor Murphy mentioning that we were looking at the films of Hitchcock during an online college course offered here in the United States, he was kind enough to reply that he was glad that his essay had been of use.

When I wrote to Professor Murphy mentioning that we were looking at the films of Hitchcock during an online college course offered here in the United States, he was kind enough to reply that he was glad that his essay had been of use.

Alma Reville, who married Alfred Hitchcock in 1926, co-scripted no less than three films for Gainsborough studios during 1928 and 1929. They were to include "The Constant Nymph", directed by Adrian Brunel and starring Ivor Novello, "A South Sea Bubble", directed by T. Hayes Hunter and starring Ivor Novello and "The First Born", directed by actor Miles Mander and starring the director with actress Madelaine Carroll.

Knowing the strained sense of humor of Alfred Hitchcok, it would only be conjecture or interpretation to claim that one McGuffin throughout his work would be the cameo shots of himself that the director inserted into his film scenes- Alma OReville in fact starred in a silent film during 1918, "The Life Story of David Lloyd George", directed by Maurice Elvey who later found renown for directing "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes". It would be even more fanciful to claim that Hitch was imitating the British Prime Minister in the cameos in order to make his wife, who followed him as a screenwriter through several films, smile. A more readily formed consensus may be that of spectatorship, that while the cameos are a cinema of attractions based on notoriety or celebrity, adding an extratectural or reflexive element, they challenge the diegesis of fictive narrative by opening the enclosed narrative space of fantasy- if only to exploit the theme of voyeurism in Hitchcock's films. Writing on Hitchcock, Michael Walker, author of Hitchcock's Motif's, delineates diegesis as "the narrative world" and the world-within-the-frame, the onscreen framed image, "conceived as a unity". By immediately discussing point-of-view editing, the diegetic experienced through the subjective shot, he places a reference point for the viewer and spectatorship. Albeit the Hitchcock cameos are incidental, wherein lies their narrative value, Walker agrees with the consensus that the MacGuffin is a subjective concern of the character that inevitably has no importance to the plot outcome whatsoever and not the blocking of a director as an extra in order to interpellate the viewer into subject identification; and yet there maybe a cat-and-mouse to the cameo shots as a motif of ordinary life and routine society; rather than something which doesn't exist, it is the concept of the total stranger.

In their full page profile on the feminity of Alma Reville, entitled Alma in Wonderland, Pictures and the Picturegoer, a British periodical, during 1925, not only avoided linking her romanticlly with her director but attempted to add an air of intrigue, reporting that she had visited Paris to buy dresses for the studio and then went on to Lake Como to where Hitchcock had already begun filming "The Pleasure Garden", it hinting that beneath her horned rim glasses, she was still a seething eligible female, who like Agatha Christie, could suddenly disappear into the flickering, darkened, silver auditoriums of the Jazz age.

Victor Seastrom

Silent Film

Silent Film

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

6:47:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Alfred Hitchcock,

British Silent Film,

Scott Lord Silent Film,

Silent Film

Monday, December 12, 2022

The Abyss (Urban Gad, Afgrunden, Denmark 1910)

Janet Bergstrom, in her paper Asta Nielsen's Early German Films, chronicles Asta Nielsen asking Urban Gad if he would write a film for her. "Afgrunden" not only secured an international audience for her but it heralded the film itself becoming an art form. Bergstrom notes Nielsen having written that she aspired to improve her acting ability by watching herself on the screen.

Although many films from the time period were adaptations of theatrical plays, "The Abyss" has no dialougue intertitles, but rather insert shots containing written letters. Both insert shots of printed material and dialougue intertitles are part of the diegesis of a silent film, whereas expository intertitles that either summarize the action or prepare the audience for it are not part of the film's diegesis, insert shots of letters bringing a more first person authorial camera that provides identification with the character.

Scott Lord Danish Silent Film

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

5:08:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Silent Film,

Silent Film 1910

Friday, December 9, 2022

Scott Lord Silent Film: The Last Performance (Paul Frejos, 1929)

The stockmarket had apparently already crashed by the time "The Last Performance", starring Conrad Veidt and Mary Philbin, was screened first run at the Park Theatre in Boston. Universal Weekly, primarily an advertising journal, after having remarked the film was "conspicuous for its camera effects and discriminating direction" tied in the New England premiere to its reception by excerpting three "leading newspapers", The Boston Globe, The Boston Herald and the Daily Record. The Daily Record mentioned the film as having been one of the two "first rate pictures" then on the marquee of the Park Theatre, the other also produced by Universal. It may be important to the history of film appreciation that the paper had written, "The Philbin-Veidt is part talkie. But in some cases, the less talk, the better the picture. This is one of those cases, for Veidt is a high rating character actor and needs no dialogue to score his points."

An earlier issue of Universal Weekly, while noting that Conrad Veidt and Mary Philbin had previously costarred together in the film "The Man Who Laughs", showed the trick photography in the film "The Last Performance" by providing a still from the film where the magician Veidt is holding Philbin in his hand. The Universal Weekly, owned by Universal Pictures Corporation, clarified itself with its captioned subtitle, "A Magazine for Motion Picture Exhibitors" and listed its editor as Paul Gulick. Letters to the editor to be published were addressed to Carl Laemmle, President. Interestingly, Author Anthony Slide gives an account of Mary Philbin having declined interviews after retirement, "Thanks to her reclusivity, she became a minor Garbo in the eyes of fans of silent film."

Silent Film Lon Chaney Bela Lugosi

An earlier issue of Universal Weekly, while noting that Conrad Veidt and Mary Philbin had previously costarred together in the film "The Man Who Laughs", showed the trick photography in the film "The Last Performance" by providing a still from the film where the magician Veidt is holding Philbin in his hand. The Universal Weekly, owned by Universal Pictures Corporation, clarified itself with its captioned subtitle, "A Magazine for Motion Picture Exhibitors" and listed its editor as Paul Gulick. Letters to the editor to be published were addressed to Carl Laemmle, President. Interestingly, Author Anthony Slide gives an account of Mary Philbin having declined interviews after retirement, "Thanks to her reclusivity, she became a minor Garbo in the eyes of fans of silent film."

Silent Film Lon Chaney Bela Lugosi

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

10:39:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Silent Film,

Silent Horror Film

Monday, December 5, 2022

Scott Lord SIlent Film: Wax Works (Paul Leni, 1924)

Paul Leni directed the expressionistic film "Wax Works" before coming to America to direct the films "The Cat and the Canary" and "The Last Warning".

Leni had worked as an art director with director Leopold Jessner on the film "Backstairs" (Hintertroppe, 1921), an "intimate drama" (Eisner) that moved "at a very slow, heavy pace" (Eisner).

Silent Film

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

10:11:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Silent Film,

Silent Film 1924,

Silent Horror Film

Thursday, November 10, 2022

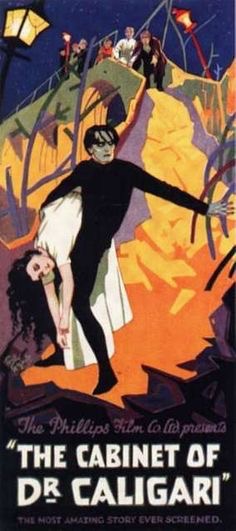

The Photoplay: Silent Movie Posters

F.W. Murnau

Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

Silent Film: The Golem

Silent Film Movie Posters

Silent Film Lobby Cards

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

2:23:00 AM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Silent Film Movie Posters

Monday, November 7, 2022

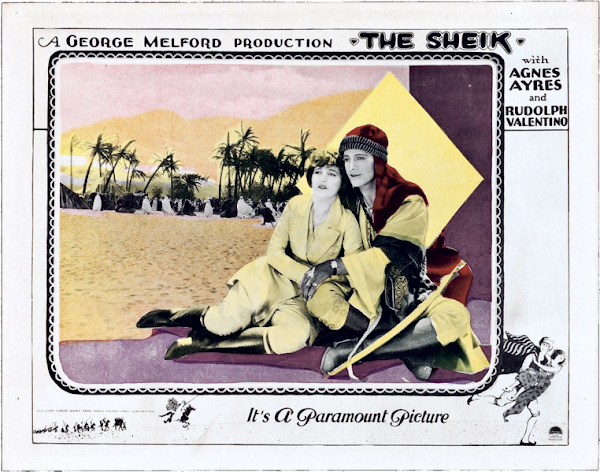

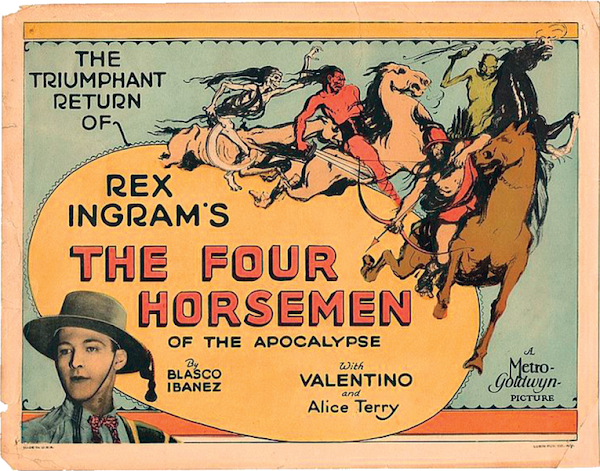

The Photoplay: Silent Film Movie Posters; Rudolph Valentino

Rudolph Valentino

Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Silent Film

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

9:23:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Photoplay,

Silent Film Movie Posters,

Silent Film: Rudolph Valentino,

Silent Movie Posters

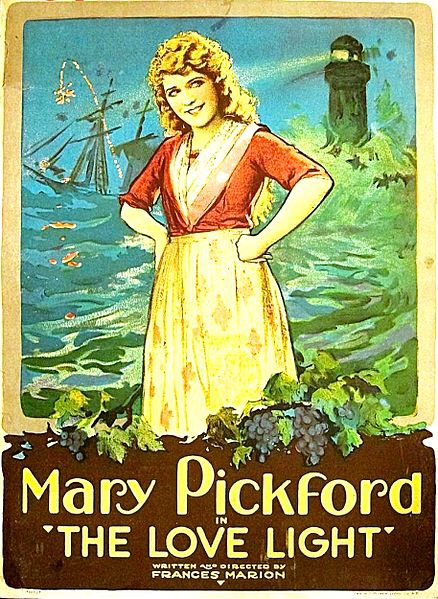

The Photoplay: Silent Film Movie Posters; Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford

Silent Film

Mary Pickford

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

8:30:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Mary Pickford,

Silent Film,

Silent Film Movie Posters,

Silent Movie Posters

Friday, October 28, 2022

Lost Films, Found Magazines: The Lobby Cards of Lost SIlent Films

Words and images that tell us what the film was about. Lost Films and Found Magazines

The article on Dartmouth professor Mark Williams was relevant, pertinent and succinct enought to require giving the name of the reporter, Kathy McCormack rather than just mentioning the Associated Press. Not being involved in film preservation itself but devoted to he study of the Photoplay, I have for years been gleaning through extratextural discourse, that which is not part of the codex of the film, to find what might have been contained in film that, for whatever reason, are now lost. When the article on lobby cards went to print, I had already had a blog entry with reproductions of lobby cards belonging to films mostly that were not lost, and being in public domain, were available through copies on my webpages, each copy of an existing film having an appended encouragement for the reader/viewer to become a film detective and find material concerning lost films-Lost Films, Found Magazines. In regard to the movie theater having similar exingencies as a museum, the lobby cards were displayed on easels and meant to be viewed by standing directly in front of them at a short distance, there being an audience reception to extratextural discourse, just as there is a "viewing" of paintings that has been changing during this century. A librarian paraphrsed by McCormack has posted that the purpose of the lobby cards were publicity and exploitation, the theater owner being an "exhibitor", but that, being aimed at the spectator, they disclosed the movie's plot, the technology soon improving to where the mood and atmosphere of the film could be surmised from the photographic images. The librarian quoted by McCormack claims that in additon to data regarding the film-and titles were often changed during production to differ from an earlier advertised title- lobby cards could often include a line of dialouge, if only one precious line of dialouge that would be a key to an entire lost film- lobby cards that were not "title cards" have been referred as "scene cards", Dartmouth College in fact had a collection of television commercials it had lent the Moving Image Rearch Center while McCormack was writing her article. The Moving Image Research Center houses material on Lois Weber and Alice-Guy Blanche. Mark Williams is presently part of he Media Ecology Project at Dartmouth College, which is digitalizing thousands of lobby cards to assist Film Preservation. Keep in mind that there have been a small number of rediscovered films, once presumed to be lost, one example being my writing on the John Barrymore version of Sherlock Holmes, which needed to be updated after the film had been found.Rudolph Valentino Silent Film Lobby Cards

Mary Pickford Silent Film Lobby Cards

Douglas Fairbanks Silent Film Lobby Cards

D.W. Griffith Silent Film Lobby Cards

Lon Chaney Silent Film Lobby Cards

Benjamin Christensen and Danish Silent Film

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

10:17:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Silent Film,

Silent Film Lobby Cards

Saturday, October 8, 2022

The Photoplay: Silent Film Lobby Cards

Rudolph Valentino

Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Silent Film Rudolph Valentino

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

2:06:00 AM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Silent Film Lobby Cards,

Silent Film: Rudolph Valentino

The Photoplay: Silent Movie Lobby Cards

Silent Film

Mary Pickford Mary Pickford Mary Pickford Mary Pickford Mary Pickford Mary Pickford Silent Film Mary Pickford

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

1:18:00 AM

No comments:

Greta Garbo Victor Sjostrom Silent Film

Mary Pickford,

Silent Film Lobby Cards

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)