| "The stylistic changes brought about by Sjostrom's moving to Hollywood may not have been as definite as film history would have it according to the paradigm. Still the story of Sjostrom was transformed by his transition to Seastrom"- Bo Florin |

When reading the play "The Image Makers" by P. O. Enquist, who passed away in 2020, Ingmar Bergman reiterated an often quoted sentiment about the actor-director Victor Sjostrom with " 'The Phantom Cariiage' is one of my most important cinematographic experiences." I needed a question that could be answered quickly when recently corresponding with, introducing myself to, rather, author Bo Florin, Stockholm University, my having asked him which was his favorite film directed by Victor Sjostrom and his favorite directed by Ingmar Bergman. He was kind enough to reply by offering to send me a copy of the book on Stiller and Garbo that he wrote with author Patrick Vonderau in that although it could be downloaded it was nicer "in the real", so in the future I might have something more than a preliminary question, one having to do with film history or film technique, at which both Stiller and Sjostrom were highly proficient. Florin wrote, "Concerning favourites: I guess my favorite Sjostrom is same as was Bergman's ('the film that he saw at least once a year': The Phantom Carriage." Although I here mention having recieved letters from Jon Wengstrom and Ase Kleveland, my correspondence has been sparse and has contained little film theory, that having been delegated to massive open online courses, some of which were on film and some of which, those on literature and history, where I have had the oppurtunity to meet my instructors in person here in the United States - so of course I was thrilled to hear from Professor Florin. In his letter, Bo Florin mentioned Patrick Vonderau, his coauthor to the volume "A Tale from Constantinople". Later in the week I recieved a letter from Professor Vonderau in which he wrote, "Thanks for your interest." |

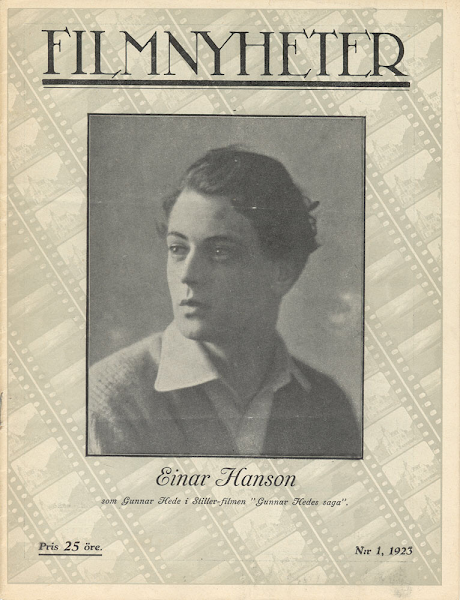

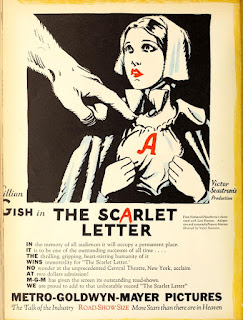

The book did come to our apartment through the mail, and I have sent Bo Florin a note of thanks, which he has recieved and acknowledged with the closing, "All the best". Included in the volume is the entire unfilmed shooting script of the film written by Mauritz Stiller and Ragnar Hylten-Cavallius which was adapted from the novel Whirlpools of Life, written by Vladimir Semitjov. While writing "A Tale from Constantinople" Florin drew upon correspondence between Stiller and Semitjov that is now housed by the archive of The Swedish Film Institute. The photoplay is spectacular and not only includes both expository and dialouge intertitles as well as the shot structure of the film but blocking instructions. Working from a shootingscript itself neglected to the extent it was thought to be "lost", Florin adresses the "singularity" of lost artefacts, what a historical piece of evidence might tell us as being unique, particularly how Enhistoria fran Konstantinopal might outline the developoment of Mauritz Stiller as an artist, his "career narrative". Bo Florin has been adept, if not brilliant, doing this with the works of Victor Sjostrom. Similarly, the careeer of F.W. Murnau has been recently seen as a "narrative". Interestingly, Florin goes so far as to speculate whether the completion of the film would have kept actress Greta Garbo in Europe.Rediscovering Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stilleras autuers of the Golden Age of Swedish Film with the Svenska Biografteatern and Skandia Filmbrya merger into Svensk Filmindustri and as Film PreservationVictor Sjostrom, in a letter to journalist Charles L. Turner quoted in the periodical Films in Review during 1960 on the occaision of the director's death accounted for his remaining taciturn about his career, the letter having had been being written twelve years earlier. "I dislike very much speaking about myself or work. And I really habe nothing to say about work finished so long ago, and left so long behind me. As a matter of fact, I had entirely forgotten most of it and was only now reminded of it by your notes. Some of the pictures....were perhaps ahead of their time. Their success was probably because the public's taste was different from that of today." Perhaps the correspondence, dated from before Victor Sjostrom the actor had appeared on screen under the direction of Ingmar Bergman, had been prompted by a flourish revival of the films Sjostrom had made at Svenska Biograteatern with Mauritz Stiller to prefigure the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film. Turner quotes Victor Sjostrom as having said,"Unfortunately, I have a very poor memory concerning my film career. Perhaps it is because when I finish a film, I have it behind me, so it just doesn't interest me anymore. Instead, I have begun to think- or it would be more correct to say - worry about my next picture." The daughter of Sweden’s greatest director of Silent Film, Victor Seastrom, passed away during the beginning of 2019. Guge Lagerwall, actress and wife of Swedish actor Sture Lagerwall, had celebrated her one hundredth birthday during January of 2018 before having died two weeks before turning one hundred and one years old. Lagerwall was the daughter of the director and Swedish Silent Film actress Edith Erastoff and, according to Victor Sjostrom one of the reasons why he returned from the United States to Sweden. The daughter of Victor Sjostrom, Guge Lagerwall wrote the screenplays to two Swedish Films, “Smeder pa luffen” (Erik Hampe Faustian, 1949) and ”Lattjo med Boccaccio” (Gosta Bernhard, 1949)- she appeared in seven films that were made in Sweden, including “Franskild” directed by Gustaf Molander in 1951, Molander having ditected the father, Victor Sjostrom, a year later, during 1952, in the film "Love" (Karleck). It may be noted that since the passing of Guge Lagerwall, two actors that starred with Victor Sjostrom in the masterpiece “Wild Strawberries” (1957) directed by Ingmar Bergman and photographed by Gunnar Fischer, are now recently deceased. Actress Bibi Andersson passed away early during 2019, actor Max Von Sydow early during 2020. Author Tommy Gustafsson is more than correct when he reluctantantly admits a canonization of Swedish Silent Film hinging on the names Victor Sjostrom, Mauritz Stiller and Selma Lagerloff. Mauritz Stiller had given Greta Garbo a lead role while in Sweden in adaptation of one of Lagerwall’s novels, an adaptation that did not go unnoticed by Lagerwall, while Victor Sjostrom had given Greta Garbo the leading role in a film version of the life of actress Sarah Bernhardt after she has arrived in America with Stiller. Although Gustafsson omits placing directors George af Klerker, Gustaf Molander and John Bruinius in a chronological relation to the forming of Svenska Filmindustri, he marks their absence in cannon that has been widely familiarized, including the discourse of what he notes Bordwell and Thompson see as a “dependence” upon landscape in Swedish film that distinguished Stiller and Sjostrom as filmmakers concerned with artistically articulating man’s place in the universe through personifying the emotion inherent in Scandinavian exterior shots and through heightening the interest in human action when confronting the elements. Shari Kiziran of Senses of Cinema recently succinctly summarized the virtue of the work of Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller as being "cinematic adaptations of Swedish literature shot on location in Scandinavia's dramatic lanscape.", but the present author would caution that it may be added that Sjostrom's use of landscape imparted a deeping of character, the Swedish Film program guide to Wild Strawberries having noted that "Using Selma Lagerlof's material, Sjostrom introduced real people into film." Jaako Seppala quotes Leif Furhammar to illustrate that Swedish Silent Film had found a literary cannon that looked to Swedish Literature for adaptations where as Finnish Silent film looked to fiction before more reluctantly adapting belltristic litterature. "The convention of including some of the original dialogue in the film adaptations' for the audience to recognize and enjoy was presumably adapted from Swedish films of the Golden era. As Eirick Frisvold Hanssen and Sofia Rossholm argue ' the use of direct quotations implies a notion of "double authorship" underlining the [the literary author's] authorial prescence' which is what Finnish sough to achive. In both countries artistic quality was synonymous with literary quality." Film was being distinguished as transnational cinema created by the personal style of the autuer. Scholar Casper Tybjerg, University of Copenhagen, in his article "The Woman's Point of View, Thora van Deken" seeks to expand the cannon of the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film by including one film directed by John Brunius, "A Mother's Fight" as belonging to cannon by being atypical by virtue of its point of view shots and flashbacks, despite its lack of Scandinavian landscape, a film that "consistently aligns us with the title character and her point of view". Co-written by Brunius and Sam Ask, the film was photographed by Hugo Edlund and starred Pauline Brunius. It is included by the Swedish Film Institute as being a noteworthy example of films that comprised the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film. In his book Masculinity in the Golden Age of Swedish Cinema, Tommy Gustafsson looks toward the viewpoints of Leif Furhammar to see competing foreign markets as a reason for the Swedish Art Film, markets that would not only compete for the attention of rivetted audiences, but for the directors of Sweden and Europe themselves. In an attempt to delineate Victor Sjostrom as a Swedish auteur, as a pioneering father of Swedish Cinema that propagated a nationalistic style, Bo Florin also asks us to keep in mind the influence of American Film on the global market, perhaps an influence that was competing with popular Danish films. Florin notes that an economic crisis that was weighing heavily upon Charles Magnusson caused the formation of a subsidiary company, AB Filminspelning, that included directors Victor Sjostrom ,Mauritz Stiller and John Brunius, a company that was unsuccessful in preventing the departure of Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller to America and a Hollywood which comprised 90% of all silent film being manufactured, easily and readily drawing the two monolithic directors away from Sweden after they had established the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film where stylistically, often the character is analyzed against the backdrop of his enviornment to deepen the film thematically. It is far from arbitrary to begin the historiography of the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film with the adaptation of Henrik Ibsen by Victor Sjostrom - Eirik Frivold Hamssen, in his volume Silent Ibsen, Transnational Film Adaptation, in the 1920's and 1930's. "In his detailed reading of the film, Bo Florin demonstrates how the alledgedlly 'national' cinematic style of the Golden Age draws on, adapts, and imitates a variety of media and that the sources used are fundamentally transnational by nature." A filmography included in the volume compiled by Maria Lund, Oslo University, lists Axel Esbensen as the designer and Nils Ellfors as the studio manager to "A Man There Was", directed by Victor Seastrom. Paul Rotha, in his volume "The Film Till Now, a survey of world cinema", had earlier made the pronouncement that the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film had "died a natural death by reason of its national characteristics of poetic feeling and lyricism." He summarized the films as having been "realized with exceptional visual beauty, being characterized by their lyrical quality of theme and by their slowness of develpoment. For enviornment, full use was made of the natural landscape value of Sweden, whilst their directors were marked by their poetic feeling." In their article Film Studies In Sweden, The Past, The Present and The Future, authors Goran Bolan and Michael Forsmann add an interesting perspective when crediting producer Charles Magnusson as a proponent of Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjostrom. They note that despite his success,that “in spite of taking up established and well-reputed plays and literary classics, the public reception was negative”, especially with the cultural elite, which coalesced into the first publications on Swedish Film, particularly those of author Frans Hallgren. Bolan and Forsmann add that admittedly Ingmar Bergman was the first Swedish director to be analyzed in light of autuer theory and that the historiography of film criticism may have left Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller out as being considered autuers. Interestingly, student Jesper Larsson, in a recent undergraduate paper for Lund University circulated on academia.org titled Tora Teje Teje, Reception and Swedishness wrote, “The Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film started with ’A Man There Was’ (Terge Vogel, Victor Sjostrom, 1917) reached its climax with ‘The Phantom Carriage’ (Korkarlen, Victor Sjostrom, 1921), and ended with ‘The Saga of Gosta Berling’ (Mauritz Stiller, 1924), whereas all these films served as a distillation of a distinctive national style. These films, often set in historical times or in rural Sweden, did not allow actresses to be glamorous in a contemporary sense and thus did not reproduce the idea of a consumerist culture.” To these, Jespersen might have added the historical dramas of Director John Brunius. Jespersen’s claim that Swedish Silent Film expressed a nationalism in its nostalgic, or rural,subject matter and a resultant camera technique to fit the exigencies of exterior location style is apparent in advertising and motion pictures both sought to reflect a visual culture with an intense interest in modernity receptive to the avaunt guarde, as is reflected not onlyin the paper Films That Sell: Motion Pictures and Advertising by Patrick Vondreau of Stockholm University but in the emergence of the relationship between advertising and Imagist poetry and Dadaist poetry. America had gone to France and created The Flapper, leaving us the view that not only were the film directors of the Swedish Golden Age tottering on seeming archaic, but that director D.W. Griffith might also have a Morality not suited to the quickening pace of the New Modern Woman, almost indicative in Lillian Gish having left to find Lars Hanson and Victor Sjostrom as though both cinemas were to compete with a short-lived German Expressionism and French Poeticism. A similar corollary between the Wasteland of Modernity and the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film is fascinatingly introduced by film historian Mark Sandberg, to quote an abstract of his paper The Outlaw and Noman’s Land: The International Circulation of Visual Repertoires, analyses the film “The Outlaw and His Wife”, directed byVictor Sjostrom by drawing attention to “the film,s insistent verticality and location shooting” by contrasting the landscapes of Neutrality to the trenchwarfare that was ravaging and devastating Europe during the four years that preceded the film’s premiere, the battlefields that perhaps may have been spied by the flanneurs while en route to the cinema forming a visual context by which audience reception took place for European viewer of the Swedish export. To keep the topic within a peer-reviewed frame, author Bo Florin dileneates the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film as 1917-1923. While reviewing Bo Florin’s volume Transition and Transformation, Victor Sjostrom in Hollywood 1923-1930 film critic Erik Hedling uses the same chronological yardstick, 1917-1923, to measure the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film, and adds,”These were characterized by elaborate landscapes depiction, heavy influences from high art, subtle acting, expressive lighting and a focus on specific devices, such as the dissolve and systematic cuts across the 180-degree line.” With the grace of a footnote to the writing of Bengt Forslund, Bo Florin extends Helding’s summarization by also characterizing Victor Sjostromas an Auteur within Swedish Silent Film, characterizing his style as displaying a “lyrical intimacy” effected by “downplayed acting, thorough work on the lighting of scenes, and mise ens scene and montage privileging a circular space with a clear center towards which movements converge.” Journalist Robert Herring for Close Up magazine in his article "Film Image: Seastrom" wrote, "Landscape is image in Seastrom". It is noteworthy that the Swedish Literature that Sjostrom and Stiller were interested in was fin-de-sicle or an extension of the turn of the century; although Victor Sjostrom's film adaptation of Ibsen's poem is a pivotal masterpiece revered for its being pivotal in the historiography of silent film, two years later, Par Lagerkvist published the essay Modern Theater, it purporting, and possibly rightly so within the literary circles it was seen, that the theater of Ibsen lacked what was needed for modern audiences. 1919 saw the publication of Par Lagerkvist's play "The Secret of Heaven" (Himlens hemlighet). Agnes von Krusensjerna that year published the volume "Helenas forsta karleck". Although a transnational cminema was emerging, it exported an older literature than that in bookstores at the time. Novelist Elin Wagner had published the novel "Asa-Hanna" during 1917. Carl Gustaf Verner von Heidenstam, albeit many of his narratives having had been been historical dramas, challenged August Strindberg during 1910, in between having published "Dikter" in 1895 and "Nya Dikter" in 1915. Bo Florin includes the film “Terje Vigen” in the cannon of the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film in part for its portrayal of the interiority of the character having been explored metaphorically, perhaps more metaphorically, ie. through metonymic representation, than in Sjostrom’s earlier films which included “Ingeborg Holm”. In the article “Confronting The Wind, a reading of a Hollywood Film by Victor Sjostrom”, Florin notes Peter Cowie as having pointed out that the film “consequently reflects the conflicts both within and between the characters in the narrative”, his adding that Fullerton “points to the dialectics in the relationship between human and landscape, which establishes analogies between them”, Fullerton having compared elements of “Terje Vigen” with those of “The Outlaw and his Wife”. It has been pointed out that "realism, psychological depth" (Joel Frykolm, DFI) were characteristics of the directing of Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller. Horack, in her paper The Global Distribution of Swedish Silent Films, succinctly and conxisely inludes "Terje Vigen" in an account of film cannon by skirting the theme of transnationalism, "The international success of 'A Man There Was' (Terje Vigen, Victor Sjostrom, 1917) convinced Charles Magnusson to start making fewer, more ambitious films, and that decision launched the Golden Age of Swedish Cinema". One British author while attempting to characterize the "series of superfilms" that followed each other in succession as being noted for the "simplicity of their composition and the true realism of their presentation of character" not only credited the adaptation of the work of Selma Lagerlof, but pointed out that Rasunda, with its two large studios, was modern when compared to European studios, as was its equipment, which further showcased the two prominent directors. Added to this is the thought that American Silent film came under a European influence and that the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film was just that in light of it being carried over into Hollywood, which was very congenially expressed in the volume The Film Answers Back: A Historical Appreciation of the Cinema, written In 1939 by E.W. Robson, who briefly, but succinctly traces the importing of film technique by Victor Sjostrom. He writes, “In Hollywood, Victor Sjostrom continued the Scandinavian tradition of reflecting upon the elements, the wind and and sky as symbolizations of the shifting nature of social life.” Bo Florin has noted that author Graham Petrie has compared the adaptation of “The Scarlet Letter” directed by Victor Sjostrom not only thematically in regard to literary tropes to the earlier adaptations of the writings of Selma Lagerlof in its examination of Puritan culture but in that his filming also permits an interplay between man and the context of nature in which man finds himself. Perhaps this is by drawing parralels between the Swedish landscape and the pioneer aspect of the spiritual remoteness from Europe that drove the Puritan onward during the first Thanksgivings in a new colony while establishing New England, if not New Amsterdam as well in what was more than rural in being a frontier ecumenically, the poet Anne Bradstreet in fact mourning the loss of a child when first arriving in the harsh New England of Hester Prynne. Graham Petrie’s volume Hollywood Destines, European directors in America 1922-1931 includes the Chapter Victor Sjostrom, ‘The Greatest Director in the World’ as well as the chapter Mauritz Stiller and others, ‘They are a Sad Looking people these Swedes’. Anne Bachman, Stockholm University, has put it succinctly for those looking for literary analysis within the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film: "nature as a trope". She adds to that the "scecificity and topographical authenticity" of the work of Julius Jaenzon that contributed to a national cienema that brought an inter-scandinavian film culture, perhaps one that overshadowed the theater of August Strindberg. To parralel this Scholar Sandra Walker outlines the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film as being between 1912-1924, a little early perhaps, when nearly seeing F.W. Murnau as a contemporary to Victor Sjostrom in a "cross-cultural context", Murnau having been indebted to the international success of Swedish Silent Films produced in the Golden Age. In a thesis entitled "A Formal and Stylistic Analysis of the early films of F.W. Murnau within the Context of Swedish and German Cinema" presented to the University of Zurich, Sandra Walker attributes this internation succes to the stylistic elements and formal structures of the films produced by specific autuers, which she compares in the directors Victor Sjostrom, Mauritz Stiller and F.W. Murnau, primarily their having "a significant use of filmed exteriors and rural landscapes" particularly in the films of Murnau between 1919-1923 before he began a period of films made in the studio- the early films of Murnau were "formally, stylisticlly and thematically similar to Swedish films produced slightly earlier at Svenska Bio and Hasselblad film and concurrently at Skandia film." She attributes the significance of outdoor landscapes to Charles Magnusson's rejection of cinema being "filmed theater" and the diffrence of having authentic locations where reality could be recorded, perhaps reproduced or imitated, by photographic images. Added to this was the size of the studio at Lidingo. Similarly, the first two Finnish directors, Erkki Karu and Teuvo Puro, are particularly noted for the use of nature as a background and landscape to complement the thematic- "Sylvi" (1913) has been particulalry likened to the film "Ingeborg Holm" directed by Victor Sjsotrom. Magnus Rosborn, archivist for the Swedish Film Institute includes “Dunagen” (1919), adapted from the writing of Selma Lagerlof to the screen by Swedish Silent Film Director Ivan Hedquvist, as well as "Ingmar's Inheritance"(Ingmarservet,1925) and "To the East" (Til Osterland, 1926), adaptations of the writings of Selma Lagerlof scripted by Ragnar Hylten Cavaliius and directed by Gustaf Molander, the former having starred Lars Hanson, Mona Martensen and Marta Hallden, the latter having starred Edvin Adolphson, to the cannon of films expressing man’s relation to the Swedish environment in the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film. The films of Swedish Silent Film directors George af Klerker, Carl Barklind and John W. Brunius were included as being from the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film by the Modern Museum of Art during 1977 for the festival entitled "Sjostrom, Stiller and His Contemporaries". Apologizing for "The Story of Gosta Berling" being the one unavailable print in the museum's selection, the press releases for the museum quote critic George Sandoul as having had the opinion that "Stiller's work was as delicate as Sjostrom's was massive." It is entirely a matter of folklore as to whether Greta Garbo msy have attended the screenings. One more recent silent film festival honoring Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller organized and curated by Jon Wengstrom, Swedish Film Institute archivist, at a European film museum not only included a screening of the “In the Chains of Darkness” (I markets bojor, 1917) directed by George af Klercker, among the twenty five Swedish Silent Films it projected, included to the programme “The Nortull Gang” (Norrtullsligan, 1923”, acknowledging its Director, Per Lindgren as an admittedly “lemsser known director”. The program to the festival noted that George af Klercker used prominent exterior shots during outdoor scenes shot on location by that these were mostly for visual effect and could not be construed as being used to develop metaphors depicting the interaction between man and nature, as often is the case with the films of Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller. Although film critcs have seen the films made in Sweden while Sjostrom and Stiller were in America as mere comedies that were "slow moving", Jon Wengstrom has cautioned against departing from the study of Swedish films that were made after 1925 by typifying the films as not being part of Sweden's Golden Age of Silent Film but by continuing with Gustaf Molander and in particular his 1926 film "Sealed Lips", the films not only being "interesting" but having "cultural value". Upon its release in 1926, Swedish film critic Begnt Idestam-Almquist had been enthusiastic, if not ecstatic about the Gustaf Molander film "Sparkling Youth" (Hon den Enda), starring Vera Voronina, Margit Manstad and Brigita Appelgren, but onky with the anticlimatic reservation that Sweden had lacked any prominent films that year (Joel Frykholm). Swedish Film archivist Magnus Rosborn recently introduced the film "A Sister of Six" (Flickorna Gyrkovics, Ragnar Hylten-Cavallius, 1926), featuring actress Karin Swanstrom, at the 2022 San Francisco Silent Film Festival. I have mentioned elswhere that the Golden Age of Silent Film was an especially silent era and that the advent of sound film had brought a return of the playwright with the dialougue of the stage to the Swedish screen, manifest in Victor Sjostrom's move from behind the camera to in front of it. Recently, John Wengstrom of the Swedish Film Institute was kind enough to reply to my letter to the Film Institute. It had been forwarded from Kristin Engtedt of the Swedish Film Institute to Mathias Rosengren and then finally to John Wengstrom. In the letter, while thanking the recipient for reading it, I mentioned that it had been over ten years since I received a letter from Ase Kleveland of the Swedish Film Institute in reply to my writing about the one hundredth birthday of actress Greta Garbo. When writing Wengstrom I had asked if The Saga of Gosta Berling, directed by Mauritz Stiller in 1924, was in tthe public domain. I had asked it almost rhetorically based on the view of the Library of Congress that every film of its age has been placed in the public domain, specifically all those filmed before 1926. Wengstrom begged to differ, noting that in Sweden, although Mauritz Stiller died in 1928, it had not been seventy years since the death of Ragnar Hylten-Cavillius, The co-writer of the script, who died in 1970. He added that The Swedish Film Institute, owner of the film, had restored the film that year and that it “regained its original aspect ratio, colors, design of inter titles and is now substantially longer than previous restorations.” During the Spring of 2018, John Wengstrom, archivist for the Swedish Film Institute, was honored by the San Franscisco Silent Film Festival for a recent restoration of “The Saga of Gösta Berling” (Mauritz Stiller, 1924), starring Greta Garbo and Lars Hanson, the new version lasting 200 minutes on screen. It is to be presented with 10 other restored silent films, among them being a previously unseen 1929 version of The Hound of the Baskervilles. My former online classmate, Emma Vestrheim, who participated with me in a class on Scandinavian film offered by the University of Copenhagen, writes that the restored version adds sixteen minutes to Greta Garbo’s debut film. Author Forsyth Hardy notes that Saga of Gosta Berling was last film Mauritz Stiller directed in Sweden before his departing to the United States in 1925. While evaluating, or comprising, a filmography of silent film of the Swedish directors of Svenska Bio and Svenska Filmindustri; Mauritz Stiller, Victor Sjostrom, John Brunius and George Af Klercker and with them the camerman Julius Jaenzon, It was refreshing to find that author Astrid Soderberg Widing tries to agree with film critic Leif Furhammar that Georg af Klerker, who began as a filmmaker at Svenska Biografteatern, can be placed with Sjostrom and Stiller as being an autuer of the pioneering art form, in that, although he seldom wrote scenarios, he added a "personal signature" to filmmaking contemporary to the other two directors- during the centennial of the two reeler in the United States and of Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller having become contemporaries at Svenska Bio. When first writing on the internet, before the deaths of Vilgot Sjoman, Sven Nykvist and Ingmar Bergman, I included this in my webpage, "Of the utmost importance is an appreciation of film, film as a visual literature. film as the narrative image, and while any appreciation of film would be incomplete without the films of Ingmar Bergman, every appreciation of film can begin with the films of the silent period, with the watching of the films themselves, their once belonging to a valiant new form of literature. Silent film directors in both Sweden and the United States quickly developed film technique, including the making of films of greater length during the advent of the feature film, to where viewer interest was increased by the varying shot lengths within a scene structure, films that more than still meet the criterion of having storylines, often adventurous, often melodramatic, that bring that interest to the character when taken scene by scene by the audience." The study of silent film is an essential study not only in that the screenplay evolved or emerged from the photoplay, but in that it is imperative to the appreciation of film technique. In my earlier webpage written before the death of Ingmar Bergman I quoted Terry Ramsaye on filent film,"Griffith began to work at a syntax for screen narration...While Griffith may not have originated the closeup and like elements of technique, he did establish for them their function." Director Ingmar Bergman had been among those who had spoken on the death of the Swedish actor- American director Victor Sjostrom Ingmar Bergman’s daughter Lena has noted that even late in life Bergman watched film extensively, his own cinema named “The Cinematograh”, which he built in a barn on Faro with three projectors, one film that he included having been Mauritz Stiller’s silent comedy “Love and Journalism”. The Museum of Modern Art during a 1977 retrospective quoted Peter Cowie, “Stiller the dramatist began to overtake Stiller the wit who made ‘Love And Journalism. His work began to resemble Sjostrom’s.” It explained that Bergman’s father was known to screen early Swedish films in his church after communion. The Museum quoted Peter Cowie, “No filmmaker before Sjostrom integrate digital landscape so fundamentally into his work or concieved of nature as a mystical as well as a physical force in terms of film language.” It added, “The tumult that threatens his heroes’ psyche corresponds, says Cowie, to the majestic power of nature and while Sjostrom’s themes are elemental, there is a tragic and noble severity in them.” While Ingmar Bergman was not unknown for his efforts toward film preservation- Widding credits him with having preserved the film Nattiga Toner directed by Georg af Klercker- Gosta Werner painstaking restored Swedish Silent Films "frame by frame", taking thousands of frames from envelopes and reassembling them before copying them into a modern print, his enlarging prints made on bromide paper and then in order to reconstruct their shot structure, comparing them to stills from several films to insure the director's sense of compostition, his also recommending the searching for of all material on the film, including a synopsis of the plot and other descriptions of what the film contained. Essential to the viewing Swedish Silent Film is the evaluation of the thematic technique of conveying a relationship between man and his environment, the character to the landscape, but before even introducing this the present author would share that there is an interesting quote form Gosta Werner the archivist from his having examined the restoring the films The Sea Vultures (Sjostrom), The Death Kiss (Sjostrom), The Master Theif (Stiller) and Madam de Thebes (Stiller), "In pre-1920 films, close ups were very rare, as were landscapes devoid of actors. Actually, shots without actors were very rare. Almost every shot included an actor involved in some obvious situation. The film told its story with pictures, but they were pictures of actors." It is with that appreciation of the art that the present author would look toward the photoplays that, with the development of both their dialogue and expository intertitles, became cinematic novels during the silent era. Werner further analyzes the early films and their mise-en-scene, making them seem as though they were in fact part of the body of work produced in the United States, "Many sequences begin with an actor entering the room and with the main actor (not always the same one) leaving the set." It is also of interest that the last film of the twenty seven that he restored was one of the most difficult in that it was a Danish detective film that lacked intertitles. Particularly because I found the cutting on the action of the actor leaving the frame of interest, if I can connect the quote to one from my own previous webpages on silent film, before reading Werner I had written, "The aesthetics of pictorial composition could utilize placing the figure in either the foreground or background of the shot, depth of plane, depth of frame, narrative and pictorial continuity being then developed together. Compositions would be related to each other in the editing of successive images and adjacent shots, the structure; Griffith had already begun to cut mid-scene, his cutting to another scene before the action of the previous scene was completely finished, and he had already begun to cut between two seperate spatial locations within the scene." It is now difficult to overlook the importance of Gosta Werner's having directed the short film Stiller-fragment in 1969. Produced by Stiftelsen Svenska Filminstitutet it showcased surviving footage from several silent films made by Mauritz Stiller in Sweden, including Mannekangen (1913) with Lili Ziedner, Gransfolken (Brother Against Brother,1913) with Stina Berg and Edith Erastoff, Nar Karleken dodar(1913) with Mauritz Stiller behind the lens and George af Klerker and Victor Sjostrom both in front of the camera, Hans brollopsnatt (1914) starring Swedish silent film actresses Gull Nathorp and Jenny-Tschernichin-Larson and Pa livets odesvager. In an interview with the San Franscisco Silent Film festival, Jon Wengstrom stressed the importance of the film "Brother Against Brother" having had been being restored and now being viewed to the understanding of the development of Mauritz Stiller as a director, it being seminal to his "evolution" as a director. Not only has Jon Wengstrom visited the United States to screen the film "Brother against Brother" directed by Mauritz Stiller, but it was interesting to read a first hand internet account from Swedish writer Mikaela Kindblom of a screening of the film he gave at the Filmhuset in Stockholm. Jon Wengstrom marked the 100th birthday of Gosta Werner by crediting him with identifying an existing fragment from Stiller’s film “Ballettprimadonna” (1915). The fillm “Ballettprimadonna”, directed by Mauritz Stiller, was restored and premiered at the Filmhuset during 2016. At the end of 2017, the Swedish Film Institutetet announced that it would be restoring the film “The Price of Betrayl” (“Judaspengar”), directed by Victor Sjostrom during 1915. In the announcement the Swedish Film Institute notes that with this film, only 16 of the 42 silent films directed by Victor Sjostrom will have been restored. m It may be noted that since the work of Gosta Werner, author Ingrid Stigsdotter has brought interest in a feminist historiography of film and a feminist archive with her article “Women Film Exhibition Pioneers in Sweden, Agency, invisiblity and first wave feminism” in which she credits Rune Waldekranz as having acknowledged the contributions of director Anna Hoffman-Undgren during 1911-1912. Astrid Soderbergh Widding, however, points to an unpublished liscentiate thesis on the cinema of attractions written by Rune Waldekranz entitled Living Pictures, film and cinema in Sweden 1896-1906, in which Waldekranz includes "an analysis between film and its audiences as well as society in general." Supplemental to the cataloging of women involved in the production of Swedish Silent Film is the contention of scholar Laura Horak that director Mauritz Stiller had broache the subject directly in his “feminist comedies” depicting “women of ambition” and presenting an “emancipated woman image”, Horak citing in particular the films “The Modern Suffradette” (1913), “Love and Journalism” (1916) and “Thomas Graal’s Best Child”. The writing of Laura Horak is also featured in the volume Not So Silent, Women In Cinema Before Sound, edited by Sofia Bull and Astrid Soderbergh Widding. There is one important recent quote from that Swedish Film Institute and the Internet, "Films considered to be lost still resurface in private collections or in foreign archives." To add to this one sentence that would instill hope that some of the remaining films can be found, Jon Wengstrom nonchalauntly glides through the fact that several of the films of Mauritz Stiller that were "previously lost films" before being restored have been "recently resurfacing in the form of foreign distribution nitrate prints". During 1970, American author Gary Carey had in fact been quoted as having said, "It is quite possible that one or more of the films in this book may sometime turn up.", the occaison having been the rediscovery of the film "The Devil's Circus" (Benjamin Christensen, 1926). Carey is responsible for having begun the search for lost silent films in the United States with the volume Lost Films, which is culled from a still collection belonging to the Museum of Modern Art Film Stills Archive, his adding plot synopsis and historical data to the photographs. He notes that with the advent of sound film, silent films were more susceptible to falling into desuetude, as was perhaps the intention when color films changed the aspect ratio used when first competeing with television. It may be fitting that, although a film version of the novel the Atonement of Gosta Berling had been planned by Skandinavisk Film Central, a company that had merged the Danish Silent Film companies Dania Biofilm and Kinogram into Palladium, between 1919 and 1921, the first part of The Saga of Gosta Berling, during March of 1924 premiered in Stockholm at The Roda Kvarn, it's second part having premiered a week later- not only is the art-deco, art-nouveau theater famous as having continued into the twenty first century, but when constructed in 1915 by Charles Magnusson, included in the first films screened in the art-house theater were those directed for Svenska Biografteatern by Mauritz Stiller, particularly, the 35 minute film Lekkamraterna, written by Stiller and photographed by Henrik Jaenzon, which starred Lili Bech, Stina Berg and Emmy Elffors, and the 65 minute film Madame Thebes, written by Mauritz Stiller and photographed by Julius Jaenzon, which starred Ragnar Wettergren, Martha Hallden and Karin Molander. It is often written that Swedish Silent Film before Molander had paid devout attention to Scandinavian landscape and its effect upon the characters in the drama, there also being an underlying sense that the conception of space, traveling through mspace according the the seasonal, played a transparent part during the recoding of the now ancient, therefore runic, Prose and Poetic Eddas. True to form the daughter of Ingmar Bergman, Journalist Linn Ullmann, included the historical place of Swedish Filmmaking in her second novel, Stella Descending. "The once thriving ostrich farm in Sundbyberg was sold, taken over by two rival companies, Svensk Bio and Skandia, who joined forces to build Rasunda Filmstad, home of the legendary film studios. Here the filmmakers Victor Sjostromand Mauritz Stiller worked alongside such stars as Tora Teje, Lars Hanson, Anders de Wahl, Karin Molonder and Hilda Bjorgstrom. Greta Garbo turned in an impressive performance in Gosta Berling's Saga in 1924, 'giving us hope for the future' to quote the ecstatic critic in Svenska Dagbladet. I can well imagine how Elias must have cursed the day his parents put their money in ostriches rather than the movies....And so it passed that Elias was part of the audience that evening in February 1934 to see When We Dead Awaken." Journalist Rilla Page Palmberg, in The Private Life of Greta Garbo published in 1931, gives a non-fiction account, "Greta called on Mr. Stiller on night after school. He was not in, but she was told to wait, as he was expected soon. Waiting in his office, she was so frightened that she felt like stealing out before he arrived. Suddenly the door opened and a tall man with a big dog came slowly into the room. He looked Greta up and down. It seemed to her as though he were looking through her. Bluntly he asked her to remove her coat and hat. Then he told her to put them back on again. After asking her a few questions he let heher know he was ready to leave." Three days later, Greta Garbo tested for Mauritz Stiller at Rasunda to make what some feel to be the last film of the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film. |

| Peter Cowie writes of a voice that was described to Vilgot Sjoman as being "so nice and gentle" it having "a quiet huskiness that makes it interesting". "'Yes, this is Stiller's room, I know for sure.' After Greta Garbo took off her glasses to show Ingmar Bergman what she looked like, her watching his face to measure the emotion of the director, she excitedly began discussing her acting in The Saga of Gosta Berling. When they returned to the room, one that had also been used by Molander, Bergman poeticlly studied her face." It had been Swedish Silent Film director Gustaf Molander, during 1923 while director of the Royal Dramatic Academy, who had been asked by Mauritz Stiller to decide upon two students to appear in his next film. Mona Martenson was already in Molander's office when Greta Garbo was called in and asked to report to Svenska Filmindustri's studios the following morning. Garbo went to Rasunda to meet Stiller for a screen test to be filmed by Julius Jaenzon, whom she happenned to meet on the train, it almost to presage the unexpected encountering she had years later with Swedish director Ragnar Ring while crossing the Atlantic. While waiting for Stiller to arrive, cinematographer Julius Jaenzon told Greta Garbo, "You are the lovliest girl I've ever seen walk into the place." In America, while being interviewed by journalist Rilla Page Palmborg in the old publicity department of M.G.M., Greta Garbo reminisced about filming with Mauritz Stiller at a time when she only saw him when he was not on his own set. "We don't rush so in Sweden. It took months to make 'Gosta Berling's Saga'. We had to wait for winter to make the winter scenes. Then, we had to wait for summer to get the summer scenes." While visiting Stockholm during 1938, Garbo asked to view the film The Saga of Gosta Berling, her having said to William Sorensen it was "the movie I loved most of all." Not incidentally, Barry Paris has since chronicled that it was Kerstin Bernadette that had brought Garbo to meet then renowned Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman, his having requested it in order for her to return to the screen in his film The Silence. One of the smaller theaters, one with 133 seats, at Borgavagen 1, is named after Mauritz Stiller, another one with 14 seats named after Julius Jaenzon, cameraman for Svenska Bio. Biografen Victor, with its 364 seats is a permanent tribute to Victor Sjostrom and the 363 ghosts that at anytime may accompany him to, perhaps in search of a new Strindbergian theater known as filmed theater, step into the past. The theater was used for the first screening of "The Gardner", the directorial debut of Victor Sjostrom from 1912, which was banned by the Swedish censor and subsequently thought to be lost untill a surviving copy was found in the library of Congress sixty eight years later. My earlier webpages, which often noted film festivals in Scandinavian, namely Sweden, had mentioned that, "In previous years Cinemateket has screened the films of Mauritz Stiller, it having published with Svenska Filminstituet the volume Morderna motiv-Mauritz Stiller I retrospektiv, under Bo Florin, to accompany the screenings. Bo Florin and the Cinematecket have also published Regi:Victor Sjostrom= Directed by Victor Seastrom with the Svenska Filminstituet." It also noted that at that time that the silent films of Sweden were also being screened on Faro, where resided the Magic Lantern and the dancing skeletons that appear when lights are lowered, possibly representative of the magician-personnas we only for a brief time borrow, identify with, while spectators; Ingmar Bergman had added a screening room to Faro that sat fifteen with a daily showing at 3:00. |