Scott Lord on the Silent Film of Greta Garbo, Mauritz Stiller, Victor Sjostrom as Victor Seastrom, John Brunius, Gustaf Molander - the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film........Lost Films in Found Magazines, among them Victor Seastrom directing John Gilbert and Lon Chaney, the printed word offering clues to deteriorated celluloid, extratextual discourse illustrating how novels were adapted to the screen; the photoplay as a literature;how it was reviewed, audience reception perhaps actor to actor.

Monday, January 30, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film: The Eclipse (Georges Melies, 1907)

Stanely J Solomon, in his volume The Film Idea, attribures George Melies with being a film pioneer, "The following film techniques were popularized- and some perhaps invented by Melies: double exposure, stop motion, fast motion, slow motion, animation, fades and dissolves."

Silent Film

Geroge Melies, A Trip the the Moon

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

5:06:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Silent Film 1907

Scott Lord Silent Film: A Trip to the Moon (George Melies, 1902)

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

5:04:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Silent Film,

Silent Film 1902

Saturday, January 28, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film: LIllian GIsh in Orphans Of The Storm (D.W. Griffith, 1921)

The photographer of the film was Hendrik Sartov. When seen by Norwegian director Tancred Ibsen, "Orphans of the Storm" was one of the films included in is decision to go to Hollywood, albeit none of the scripts he wrote while there were realized.

William Everson, in his volume American Silent Film, perhaps sees the significance of "Orphans of the Storm" lying perhaps in tits improtance to us more than as a steppingstone for D.W. Griffith. He writes, "While it did well, Orphans of the Storm was not the box-office blockbuster that Griffith expected and needed badly. Because it was neither a financial landmark nor an aesthetic advance over his previous films, it is usually dismissed by historians (even the few responsible one's) as representing 'Griffith in Decline'." Everson reports that after the premiere, which he spoke at and which was attended by Lillian and Dorothy Gish, Griffith cut "the more harrowing scenes" from the film, including close-ups of vermin crawling over Dorothy Gish and shots from the execution scene. And yet, Everson is certainly correct that the film showcases the directorial skills of D.W. Griffith. Everson continues, "The detail shots in battle scenes (troops moving into formation, close ups of pistols being loaded and and fixed) gave them a documentary quality which mde them explicable as well as ezciting."

D.W. Griffith

Silent Film

Intolerance

Scott Lord Silent Film: One Exciting Night (D. W. Griffith, 1922)

The photographer to the film “One Exciting Night” was Hendrik Sartov.

After having directed Carol Dempster in “One Exciting Night” (Eleven reels), D.W. Griffith, by then having become a producer for United Artists, followed in 1922 by directing Dempster in the film “The White Rose” (twelve reels) with actress Mae Marsh.

Silent Film

Silent Film

Silent Film

Silent Film

Thursday, January 26, 2023

Scott Lord Swedish Silent Film: Synd (Gustaf Molander, 1928)

Swedish silent film director Gustaf Molander had in fact been at the Intima Theatern from 1911 to 1913.

In regard to the film “Synd”, Forsyth Hardy writes, “The Merzback influence had helped to scale down the Strindberg drama into a thriller.” In his volume Scandinavian Film, Forsyth Hardy, while outlining that there had been a turn to a more theatrical style in cinema just prior to the advent of the sound film and, for economic reasons, an attempt to make films that could be exported, mentions that there had been a departure from the tradition of the Golden Age of Swedish silent film that conversely gained little recognition outside of Sweden. Paul Merzbach had become head of the script writing department and produced films directed by Gustaf Molander that were, according to Hardy, “superficial rootless products”.

Starring in the film “Synd” (Sin, 1928) were Lars Hansonand Elissa Landi. The cinematographer of the film was Julius Jaenzon with Ake Dahlquist as assistant camerman.

Gustaf Molander

Gustaf Molander

Scandinavian Silent Film

Lars Hanson

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

1:09:00 AM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Gustaf Molander,

Scandinavian Film,

Scott Lord,

Scott Lord Silent Film,

Scott Lord Swedish Silent Film,

Silent Film 1928

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

Scott Lord Swedish Silent Film: Revelj (George af Klercker, 1917)

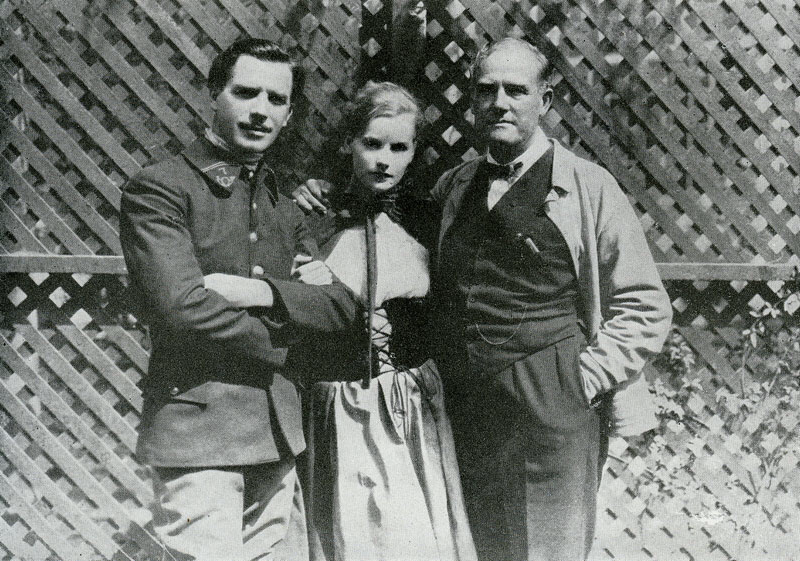

Directed by George af Klerker in 1917, the film "Revelj" starred actresses Mary Johnson, Lily Croswin and both Gertie Lowestrom and Gerda Bjorne in the first film in which either were to appear onscreen. The film was photographed by Carl Gustaf Florin and the screenplay was written by Carl Svensson-Graner. That year Swedish silent film director George af Klerker also directed actress Mary Johnson in the film "The Suburban Vicar" (Forstadprasten), in which she starred with Concordia Selander and Lilly Graber. During 1917 George af Klercker also directed the film "I Morkets Bojor" one of the only two films in which actress Sybil Smolova had appeared. "Vagen Utter", in which George af Klercker had a year earlier during 1916 had directed Sybil Smolova, is presumed to be lost, therebeing no surviving copies of the film. Scandinavian Silent Film Silent Film Silent Film

Friday, January 20, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film: Mary Pickford in 100% American (Arthur Rossen)

"She was nice and she was sweet, say many to explain the phenomenon...The reason can only be found in by relating the star to the social and cultural background of the time...Only the American civilization, a civilization materially in advance of the rest of the world could have produced Mary Pickford. We must try to realize the impact of Mary Pickford's appaearance and acting upon the consciousness of the world's population as it existed around 1909."

It is certain that the beginnings of the star system had made Mary Pickford an attractive commodity by 1918 when we had reluctantly taken part in the continuance of an unexpected war- the quote may point to the historical context and extratextural discourse that is a dynamic of that star system. A starsystem that has been called "a culture of celebrity", the silent film era has kept some of its first impressions as long lasting, albeit some were fleeting, authors often making comparisions between fixed points in the firmament, especially when introducing the newest foreign arrival, in as much as an actress was now considered "Sweden's Mary Pickford", or when there was a common theme between Gish, Pickford and Mae Marsh. Although far from the earliest example of film criticism, the quote is from a volume titled The Film Answers Back, an historical appreciation of the cinema. Authored by E.W. + M.M. Robson, it was published in 1939. Oddly, the review of the films of the actress begins to address, not gendered spectatorship, but her femininity within the expectations drawn by a woman on the screen and how it related to being a Suffragete. Notwithstanding, it was that Mary Pickford by then was sought after and Parmount Press Books from 1917 describe her having sold Liberty Bonds as a result of a request from United States Secretary McAdoo, her wearing the insignia of an honarary colonel. The pressbooks announced, "Famous Artcraft Star Stops All Film Activities When Call Comes To Help Country and Flag by Selling Liberty Bonds". Prior to the short 100% American, Mary Pickford released the full legnth feature film "Johanna Enlists", adapted by Frances Marion from the short story The Mobilizing of Johanna, published in 1917. Returning to the year the film was made and to contrast the on screen images with the extratextural discourse of the off screen lives of actresses, Mary Pickford and Linda A. Griffith during 1918 were given back to back bylines in the periodical Film Fun. The article written by Mary Pickford was a look toward the future of filmmaking, and thereby necessarily lending an assessmeMnt of the time period and historical context, her praising the work of Cecil B. DeMille. In turn, Linda A Griffith followed in the same issue and neglected entirely the gendered spectatorship that would view the talented Mary Pickford. She rather discusses Mary Pickford's salary with the claim that her husband, D.W. Griffith, saw her as being underpaid. Griffith's wife subtitled part of her 1918 article with "Adequate Payment for Good Work". There is almost an objective correlative, or perhaps a suspension of disbelief, in our agreement to walk into the theater and enter fictional worlds that the director's wife acknowledges, neglecting those fictional scenarios, while bringing us a real life Mary Pickford, who in fact later returned to sell bonds for the Defence Department during 1953. Silent Film Silent Film

It is certain that the beginnings of the star system had made Mary Pickford an attractive commodity by 1918 when we had reluctantly taken part in the continuance of an unexpected war- the quote may point to the historical context and extratextural discourse that is a dynamic of that star system. A starsystem that has been called "a culture of celebrity", the silent film era has kept some of its first impressions as long lasting, albeit some were fleeting, authors often making comparisions between fixed points in the firmament, especially when introducing the newest foreign arrival, in as much as an actress was now considered "Sweden's Mary Pickford", or when there was a common theme between Gish, Pickford and Mae Marsh. Although far from the earliest example of film criticism, the quote is from a volume titled The Film Answers Back, an historical appreciation of the cinema. Authored by E.W. + M.M. Robson, it was published in 1939. Oddly, the review of the films of the actress begins to address, not gendered spectatorship, but her femininity within the expectations drawn by a woman on the screen and how it related to being a Suffragete. Notwithstanding, it was that Mary Pickford by then was sought after and Parmount Press Books from 1917 describe her having sold Liberty Bonds as a result of a request from United States Secretary McAdoo, her wearing the insignia of an honarary colonel. The pressbooks announced, "Famous Artcraft Star Stops All Film Activities When Call Comes To Help Country and Flag by Selling Liberty Bonds". Prior to the short 100% American, Mary Pickford released the full legnth feature film "Johanna Enlists", adapted by Frances Marion from the short story The Mobilizing of Johanna, published in 1917. Returning to the year the film was made and to contrast the on screen images with the extratextural discourse of the off screen lives of actresses, Mary Pickford and Linda A. Griffith during 1918 were given back to back bylines in the periodical Film Fun. The article written by Mary Pickford was a look toward the future of filmmaking, and thereby necessarily lending an assessmeMnt of the time period and historical context, her praising the work of Cecil B. DeMille. In turn, Linda A Griffith followed in the same issue and neglected entirely the gendered spectatorship that would view the talented Mary Pickford. She rather discusses Mary Pickford's salary with the claim that her husband, D.W. Griffith, saw her as being underpaid. Griffith's wife subtitled part of her 1918 article with "Adequate Payment for Good Work". There is almost an objective correlative, or perhaps a suspension of disbelief, in our agreement to walk into the theater and enter fictional worlds that the director's wife acknowledges, neglecting those fictional scenarios, while bringing us a real life Mary Pickford, who in fact later returned to sell bonds for the Defence Department during 1953. Silent Film Silent Film

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

3:38:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Mary Pickford,

Silent Film

Sunday, January 15, 2023

Friday, January 13, 2023

Scott Lord Swedish Silent Film: Vem Dömer (Who Should Judge?, Victor Sjostrom, 1922)

In Sweden, during 1922, Victor Sjostrom directed Jenny Hasselqvist in “Love’s Crucible”, co-scripted by Hjalmer Bergman and photographed by Julius Jaenzon. Nils Asther and Gosta Emmanuel appear on screen in the film. Author Forsyth Hardy, in his volume Scandinavian Film notes that the film was "an elaborate and spectacular historical film". Forsyth Hardy implies that "Vem Dormer" was not only an example of the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film but an overwhelming attempt to save it, it having been an expensivefilm to make in hooe of regaining an overseas audience that had begun to lose interest in serious Swedish Films. "All the resources of the newly completed Rasunda Studios were mobilized to make the spectacular Vem Dormer."

During the following year, 1923, Jenny Hassellquist starred in another collaboration between Victor Sjostrom and Hjalmer Bergman, the Film “Eld Ombord” (“The Hellship”)in which she appeared on screen with Victor Sjostrom, while under his direction. Actor Matheson Lang and actress Julia Cederblad appear with her in the film, which was photographed by Julius Jaenzon.

Victor Sjostrom

Victor Sjostrom Playlist

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

1:14:00 AM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Scandinavian Film,

Scott Lord Swedish Silent Film,

Scott Lord Victor Sjostrom,

Swedish Silent Film,

Victor Seastrom,

Victor Sjostrom

Scott Lord Swedish Silent Film: Hans nåds testamente (Victor Sjostrom, ...

During 1919, Victor Sjostrom directed the film “His Lord’s Will” (“His Grace’s Will” “Hans nads testamente”) from the writings of Hjalmer Bergman. Photographed by Henrik Jaenzon, it starred actresses Greta Almroth and Tyra Dorum. In bookstores during 1919, God’s Orchid, written by Hjalmer Bergman appeared published in its first edition, followed in 1921 by the novel Thy Rod, Thy Staff and in 1930 by Jac the Clown. The film was remade in 1940 by Per Lindgren, scripted by Stina Bergman and starring Barbra Kollberg and Alk Kjellin.

Scott Lord Scott Lord Victor Sjostrom

Scott Lord Silent Film: (The Hell Ship 1923, Victor Sjostrom)

"The Hellship" (Eld Omboard), directed by Victor Sjostrom and co-scripted by Victor Sjostrom and Hjalmer Bergman, starred actresses Jenny Hasselqvist, Julia Cederblad and Wanda Rothgardt.

Victor Seastrom

Victor Sjostrom

Scott Lord Silent Film: Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy (1962)

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

12:58:00 AM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Silent Film,

Silent Film Comedy

Monday, January 9, 2023

Scott Lord Swedish Silent Film: Synnöve Solbakken (Brunius, 1919)

The first adaptation based on the novel by Bjornstjerne Bjornsons, the film was co-scripted by John Brunius and Sam Ask, John W. Brunius having directed the film. It starred Karin Molander and Lars Hanson, who eventually married in 1922. Author Peter Cowie describes Karin Molander as being "evanescent" in the film. During 1919, John Brunius and Sam Ask also collaborated on the script to the film “Ah i, Morron Kvall”, which Brunius directed.

Silent Film

Scandinavian Silent Film

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

5:03:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

John Brunius,

Scandinavian Film,

Scott Lord,

Scott Lord Silent Film,

Silent Film,

Svenska Filmhistoria,

Swedish Silent Film,

Swedish Silent Film John Brunius

Gustaf Molander

During 1927 Gustaf Molander directed the film "Sealed Lips" ("Forseglade lappar") with Wanda Rothgardt, Mona Martensen, Stina Berg and Karin Swanstrom. It was the first film to be photographed by Ake Dalquist. Film Daily in the United States reviewed the film during 1928, writing, "Mona Martenson looks as if she will be heard from after developing more screen experience....Others, evidently Swedish players also all competent for their roles...Some of the technique employed is stilted, but fine directorial touches and an interesting story quite capably acted makes it a novel diversion. Fair program if cut and retitled."

During 1927 Gustaf Molander also directed the film "Discord/His English Wife" ("Hans engleska fur") with Margit Manstad, Wanda Rothdardt, Lil Dagover and Margit Rosengren in what would be her first appearance on screen. In the United States Motion Picture News Booking Guide reviewed the film "His English Wife/Discord" as a "Society Drama" relating its theme as "Avaricious relations force girl to marry wealthy farmer. Used to city life she soon tires of his home and returns to city. They come to an understanding only after the wife finds her gaiety false and her love for her husband the main thing." Film Daily in the United States, where Pathe had acquired the film for distribution and advertised it as though it were their production, opined that the film was a "Society drama with European background and treatment that is effective in many instances. No very familiar names but several worthy performances." Among those performances the magazines deemed worthy of reviewing were "Gosta Ekman, the handsome blond man about town, Uhro Somersalmi good at times but occasionally given to to overdone guestures. Stina Berg very comfortable and likable housekeeper." The magazine looked favorably at Molander's direction.

Peter Cowie, in his volume Scandinavian Cinema, evaluates Molander's direction of the film with, "Molander's direction fails to bring the London sequences alive, but once on home territory his flair for outdoor filming enhances the mood." Cowie summarizes the unfolding of the narrative with "The film degenerates into a drawing room drama." Forsyth Hardy sees the films as comedies that unduly come under the heavy influence of Paul Merzback of Svensk Filmindustri, who was looking for a more international audience, and who would bring a frivolity to early sound films made in Sweden that now would seem far too typical. When reviewed in the United States, it was written that "His English Wife" was a film in which "the acting is of the school that believes in tapping fingers and clenched hands" and when "Sealed Lips" was reviewed it was written that "the direction goes back to the stand-gaze-and-hark acting of the old days." Hardy reverses his sentiment on Molander by later writing, " His 'Malapiratrer' (1923) adapted from a comedy from Sigfried Sibertz, was a fresh and spontaneous piece of work with some pleasant acting by Einar Hanson and Inga Tibland." Actress Stina Berg had appeared in "Constable Paulis Easter Bomb/The Smugglers" (Polis Paulus skasmall, 1925), directed by Gustaf Molander and also starring Guken Cederberg and Lilli Lanni.

In 1928, Gustaf Molander filmed "Woman of Paris" ("Pariskor") with Ragnar Arvedson,Ruth Weyher nd Karin Swanstron. It was photographed by Julius Jaenzon.

Author Forsyth Hardy includes "Triumph of the Heart" (Hjartes Triumf, 1929) among those films made under the influence of Paul Merzbach which "made little impression on the film going world outside Sweden and they contributed nothing to the tradition built up during the Sjostrom-Stiller period." (Hardy)

Swedish Silent Film

Silent Film

Silent Film

Greta Garbo

Wednesday, January 4, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film: Sarah Bernhardt in Les Amours de la reine Élisa...

Directing in 1912, Louis Mercatan had filmed stage actresss Sarah Bernhardt for four reels using only long static shots; there are twenty three scenes in the film and of twenty two intertitles, only three are interpolated. Most summarize the dialogue and its consequence to the action untill the exclamation in scene twenty one, “May God forgive you, I never will.” While discussing the advent of sound film and its acceptance by French filmmakers, the periodical Exhibitor's Daily Review abjured its readers that the would be "reminded that Sarah Bernhardt was the first star of the first movie drama ever produced."

A year later, in 1913, D.W. Griffith, having already adopted the practice of making two-reelers, directing the first American four-reel narrative, “Judith of Bethulia”, starring Blanche Sweet. Louis Mercanton directed Sarah Berhardt again duriing 1913, reverting back to a two reel running length with the film "Adrienne Lecourver, An Actress's Romance", the film presently presumed to be lost,with no surviving copies.

All five or six reels of the 1915 film "Jeanne Dore", starring Sarah Bernhardt and written and directed by Louis Mercantan are presumed to be lost. It mas included among many of the Bluebird Photoplays during the company's brief existence during the first decade of the twentieth century. Greta Garbo is quoted by Sven Broman as having said, "I know that he courted Sarah Bernhardt and wanted to write plays for her...but Strindberg still managed to get Sarah Bernhardt to do a guest performance in Stockholm in La Dame aux Camelias at the Royal Dramatic Theatre. There are reports of surviving existing copies of the one reel 1909 film "La Tosca" starring Sarah Bernhardt and Eudourdo Max. Sara Bernhardt plays herself, as do Sir Basil Zahrof and Maurice Zahrof in the two reel "Sara Bernhardt a Belle Isle" from 1912. "Mothers of France" (1917) would be the last film to feaure the The Divine Woman, Sarah Bernahrdt.

Silent Film

Silent Film playlist

Silent Film playlist

Monday, January 2, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film:The Death of Rudolph Valentino (Pathe Newsreel)

The volume “Valentino As I Knew Him” was quickly published in 1926 by S.George Ullman and the A.L.Burt Company. Ullmangives an account of his reminisces of Rudolph Valentino and his conversations with him. “The priest came at my summons and was alone with the dying man for some time...Rudy forced a smile so wan that it belied his brave words and said, ‘I’ll be alright’...’Don’t pull down the blinds! I feel fine. I want the sunlight to greet me.’...These were the last intelligible words he ever spoke.”

The periodical Film Daily during August 1926 quoted actress Mae Murray as having said, "Valentino's greatest quality was a deep sincerity underlying an enormous strength of character." It quoted Lon Chaney as having said, "I don't know when a piece of news so affected me as Valentino's death." John Gilbert was to say, "The death of Valentino is a terrific loss to the screen." Director Clarence Brown said, "Valentino's death is the biggest loss the screen has ever had." Actress Alice Terry gave a heartffelt, "As one who played with Valentino in his first two successes, 'The Four Horsemen' and 'The Conquering Power', his loss to me is a very keen one personally."

Silent Film

Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino Rudolph Valentino

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)