Scott Lord on the Silent Film of Greta Garbo, Mauritz Stiller, Victor Sjostrom as Victor Seastrom, John Brunius, Gustaf Molander - the Golden Age of Swedish Silent Film........Lost Films in Found Magazines, among them Victor Seastrom directing John Gilbert and Lon Chaney, the printed word offering clues to deteriorated celluloid, extratextual discourse illustrating how novels were adapted to the screen; the photoplay as a literature;how it was reviewed, audience reception perhaps actor to actor.

Sunday, April 30, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film: Lon Chaney in The Scarlet Car (DeGrasse, 1917)

Directed by Joseph de Grasse during 1917, "The Scarlet Claw" starred Lon Chaney, Franklin Farnum and Edith Johnson.

During 1917, Joseph de Grasse also directed Franklin Farnum and Lon Chaney in the film "Anything Once", with actress Marjorie Lawrence. Although the film is not yet presumed to be lost, it is unknown if any copies now survive.

Silent Film

Lon Chaney

Lon Chaney

Friday, April 28, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film: Sage Brush Tom (Tom Mix, 1915)

Tom Mix was credited as having written, directed and starred onscreen in the 1915 film "Sage Brush Tom", produced by Selig Polyscope. Apearing in the film were actresses Goldie Colwell and Victoria Forde.

Silent Westerns

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

9:50:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Silent Film,

Silent Film 1915

Monday, April 24, 2023

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film: The Unbeliever (Alan Crosland, Edison Company, 1918)

The Edison Company released its last film as a studio, "The Unbeliever" (Alan Crosland, six reels) in 1918. The periodical Motion Picture News seems to have been kept in the dark that it would be the swan song of the studion, claiming that the Edison Company viewed the film as their "greatest contribution to the screen". "The Unbeliever" starred Margueritte Courot, Kate Lester and Eric von Stroheim.

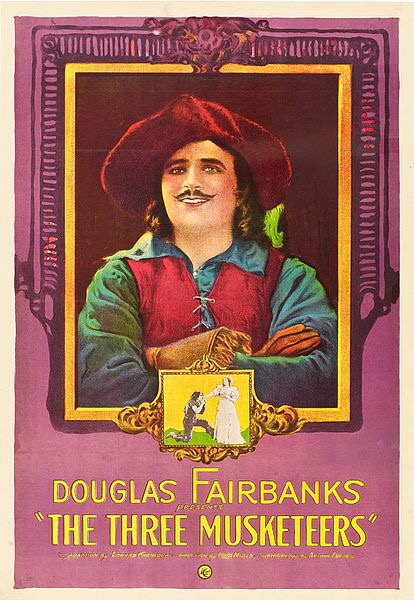

Not incidentally, the term "one sheet" used to describe the standard size of movie posters began with the Edison photoplay; it was a size of approximately 27 inches by 41 inches often included a synopsis of the plotline of the film. Silent Film Edison Film

Not incidentally, the term "one sheet" used to describe the standard size of movie posters began with the Edison photoplay; it was a size of approximately 27 inches by 41 inches often included a synopsis of the plotline of the film. Silent Film Edison Film

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

11:37:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Silent Film,

Silent Film 1918

Saturday, April 8, 2023

Praesidenten (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1919)

Although "The President" (Praesidenten, 1919), written and directed by Carl Th. Dreyer, photographed by Hans Vaage, and having starred Elith Pio and Olga Raphael-Linden, is not always distinguished as remarkable, it is one of the only two films that Carl Th. Dreyer made in Denmark, his later establishing a small body of work that would be indelible upon filmmaking, hi films, disparate stylistically, each differeing in their use of technique. Dreyer has been quoted as having remarked upon his having tried to find a style that would have value for only a single film. Casper Tybjerg, University of Copenhagen, highlights the use of "intricate flashback narrative structure" in Dreyer's directorial debut.

In his article "Forms of the Intangible: Carl Dreyer and the concept of Transcendental Style", Scholar Casper Tybjerg looks at Paul Schraeder's concept of there being an "aesthetic dimension of religious films" and accordingly a transcendental style to express spiritual experience by "stylizing" reality.

Silent Danish Film Danish Silent Film

Thursday, April 6, 2023

Wednesday, April 5, 2023

Scott Lord Silent Film: The Great Train Robbery (Porter,1903)

In the autobiographical reminiscences William N. Selig printed in Photoplay Magazine during 1920, Selig, perhaps almost graciously, credits Edison with the "first single reel picture containing a story in continuity", although he adds that "The Great Train Robbery" was only 800 feet and that he was soon on Edison's coattails with films of his own of length equal to it. Interestingly, Selig recounts in the article director Frank Boggs as "the real pioneer in photographic reproduction", his during 1908 releasing a one reel film every week; Selig claims Boggs was assasinated on the Selig Studios during 1912. Vladimir Petric in A Visual/Analytical History of Silent Film (1895-1930), Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, notes Porter's "The Great Train Robbery" as a "primitive use of parralel editing to dramatize the narrative". Not only is this in sharp contrast to the earlier cinema of attractions that relegated storytelling to the act of display, but the film is significant as the first film made in the Western genre. It is uncanny that the closing shot, as a subjective shot, is an attraction, something static and something dispalyed, urging the spectatator to draw and shoot back. Patric Vonderau and Vinzenz Hedigar have written, "The visuality of the display, however, is still indispensible to its effect."- albeit their recent volume, Films That Work, is primarily concerned with international industrial films.

Author Nicholas A. Vardac opines that it was the films of Edwin S. Porter that D.W. Griffith aquired the technique of viewing the shot within its context as a "syntax for the melodrama". Whether crosscutting began with Edwin S. Porter and "The Great Train Robbery", a film which is attributed as having used croscutting in the volume The Film Idea, written by Stanley J. Solomon, or whether it was more properly developed by D.W. Griffith around 1908, as with the parallel editing in the 1907 films "The Greaser's Gauntlet" and "The Fatal Hour" (Phillipe Gauthier, Harvard University), author Stanley Solomon points out that crosscutting was intrinsiclly cinematic, rather than dramaturgical or theatrical by describing it as "a technique suitable to the form of cinema but unnatural to the form of nineteenth century stage drama, which was at that time a significant influence on the new media." A recent online film class on how to "read" a film from described the film as being comprised of "seperate shots of non-continuous, non-overlapping action" while being careful to designate the film as an early example of crosscutting.

Film historian Charles Mussur, in Before the Nickelodeon :Edwin S. Porter, writes, "Porter's film meticulously documents a process...The film's narrative structure, as Gaudreault notes, utilizes temporal repetition with an overall narrative progression." As narrative it was essentially a reenactment film. He adds that "Porter exploited procedures that heighten the realism and believabilty of the image" (David Levy).

It is apparent that "The Great Train Robbery" was filmed not only in the studio, but on actual locations, including in fact a train Porter had borrowed in New Jersey; it also apparent that "The Great Train Robbery" released during 1904 by Sigmund Lubin also combined scenes filmed both outdoors and inside the studio, the film also concluding with a close up of an outlaw. Catalougues "free upon request" featuring "Lubin's Latest Hits" list Lubin's "The Great Train Robbery" as running 600 ft, there being sixteen seperate scenes to the film. The 1903 Edison Manufacturing Company catalougue lists the running legnth of Edison's "The Great Train Robbery", a "sensational and highly tragic subject", as 740 ft, the film divided into fourteen scenes.

The sequel to "The Great Train Robbery", titled "The Little Train Robbery" (1905) although directed by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Company, is a parody, and features an all child actor cast.

Silent Film Silent Film D. W. Griffith

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

9:01:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

Silent Film,

Silent Film 1903

Scott Lord Shakespeare in Silent Film: The Taming of the Shrew (D.W. Gri...

Robert Hamilton Ball, in his volume Shakespeare on Silent Films explains the increase of adaptations of Shakespeare's plays during 1908-1911. "By 1908, the story film had become general...Moreover, his variety of scenes fitted well with new conceptions of scenario structure, with cutting and editing." Ball notes that D.W. Griffith follows The Taming of the Shrew chronologically but only uses four or five scenes to explicate its central incidents. Ball points out that there are no explanatory intertitles used in the film, which could have been used in the exposition of plot, but that Shakespeare was also at liberty to use long passages of supplementary dialougue when writing plays. He offers a claim that there were ten Shakespearean films made in the United States alone during 1908 while noting that in regard to recent transnational studies of the recent historiography of silent film that "there were no doubt cross-influences from country to country." Only one of these adaptations were from the Kalem Studios, As You Like It and only one was produced by Biograph. The is scant information pertaining to the film Julius Caesar, produced that year by Lubin. The film adaptation of "The Taming of the Shrew" filmed in Great Britain during 1911 by Frank R Benson starring Constance Benson is a lost film, of which there are no surviving copies.

Actress Florence Lawrence had come to Biograph from Vitagraph, which had produced several adaptations of Shakespeare that year, and camerman Arthur Marvin was being trained by innovator Billy Bitzer.

King Lear

Shakespeare in Denmark

Biograph Film Company

Shakespeare in Denmark

Biograph Film Company

Scott Lord Silent Film: Frankenstein (J. Searle Dawley, Edison Manufactu...

Authors Dennis R Cuthcin and Dennis R. Perry in their work "The Frankenstein Complex, when the text is more than a text" view the silent film "Frankenstein" as having been inspired by several stage adaptations, specifically Presumption, or the Fate of Frankenstein, which, produced in 1823 by Richard Brinkley Peak, may have been remote to the Edison Studios in New Jersey, as may have been the other fifteen theatrical adaptations of "Frankenstein" produced before 1851. The University of Pennsylvania presently includes Henry M. Milner's The Demon of Switzerland (1823) and The Man and the Monster (1826) among them, but admits that several theatrical adaptations were burlesque or musical comedy.

That intertitles were at first often explanatory shows the beginning of a narrative cinema. During an early scene of the silent film "Frankenstein" (J. Searle Dawley, Edison, 1910, one-reel) there is, in between scenes, an expositiory intertitle that uses a close shot of a letter to develop plot and character within the narrative, a form of the epistolary form of the novel transferred on to the screen. A similar insert shot is used in the film "A Dash Through the Clouds" (1912).

J. Searle Dawley directed at Edison Film Manufacturing Company untill 1913, when he joined Edwin Porter at Famous Players Company, where he directed actress Marguerite Clark.

Silent Film

Silent Film Silent Horror

Scott Lord Silent Film: Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922)

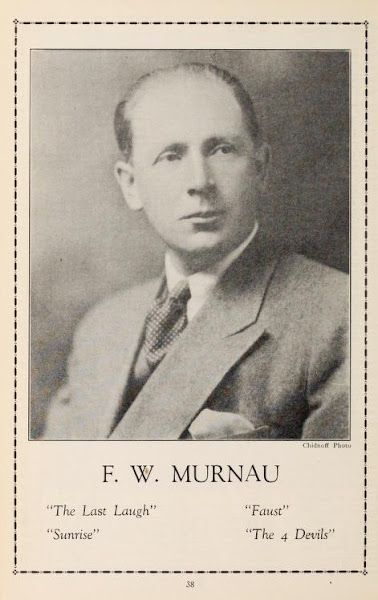

The film adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson's account of Dr.Jekyll and Mr. Hyde directed by F.W. Murnau during 1920 is presumed lost, with no known existing copies of the film. "The Head of Janus" (Der Janus Kopf, Love's Mockery) had starred Conrad Veidt amd Bela Lugosi and is credited with having been one of the first films to include the use of the moving-camera shot. F.W. Murnau made 21 feature films, 8 of which are presumed lost, with no surviving copies. Included among them is the 1920 horror film "The Hunchback and the Dancer" (Der Bucklige und die Tanzerin) photographed by Karl Freund.

Lotte H. Eisner, in his biography titled Murnau, looks at a scene change to the shooting script of "Nosferatu" written by Henrik Galeen made by the director, F.W. Murnau, but adds that few additons and revisions to the original script were made by Murnau. "Sometimes the film is different than the scenario though Murnau had not indicated any change in the script...But there is a suprising sequence in which nearly twelve pages (thirteen sequences) have been rewritten by Murnau."

Lotte H. Eisner analyzes the film "Nosferatu" in his companion volume to his biography of Murnau, The Haunted Screen. "Nature participates in the action. Sensitive editing makes the bounding waves foretell the approach of the vampire." Eisner later adds, "Murnau was one of the few German film-directors to have the innate love of the landscape more typical of the Swedes (Arthur von Gerlach, creator of Die Chronik von Grieshums, was another) and hes was always reluctant to resort to artifice." Murnau had visited Sweden where the cameras being used were made of metal rather than wood, which aquainted him with techniques that were in fact more modern. Author Lotte H Eisner, in his volume Murnau writes of F.W. Murnau viewing the films of Victor Sjostrom and Mauritz Stiller "when he made 'Nosferatu', the idea of using negative for the phantom forest came from Sjostrom's 'Phantom Carriage', which had been made in 1920. Above all, he had a love-hatred for Mauritz Stiller, whose 'Herre Arne's Treasure' he couldn't stop admiring."

Not only can we look at Murnau's film to compare and contrast its use of landscape and location to that of Swedish Silent Films, but the Wisconsin Film Society during 1960 pointed out that its narrative was situated in a different century. "Murnau probably felt that by transferring the action to the year 1838 he would have an atmosphere more condusive to the supernatural. Because of the distance in time, an audience is perhaps more willing to employ its 'suspension of disbelief'." The Film Society mentions F.W. Murnau having filmed the Vampire's carriage in fast-motion for effect, an effect which it felt had been lost on the audiences of 1960. It conceded that shooting on location brought the film "far from the studio atmosphere", but hesitated, "Although frequently careless in technical details (camerwork, exposure, lighting, composition, and actor direction) it had variety and pace."

Lotte H. Eisner, in her volume Murnau, writes, "As always, Murnau found visual means of suggesting unreality". Professor David Thorburn, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, expresses aprreciation and gratitude for the author's writings pointing out that "her arguments in The Haunted Screen are still widely accepted." In regard to the expression of unreality, David Thorburn sees Expressionism as having been typified by "distortion and surreal exaggation" as well as having been "interested in finding equivalents for he inner life, dramatizing not the external world, but the world within us." If not the first horror film, Thorburn delegates "Nosferatu" to being an "origin film" and as "the film in which we can see Murnau freeing the camera.....no one had ever used the camera outdoors more effectively up to this time than Murnau". Lotte H Eisner, in The Haunted Screen writes, "The landscape and views of the little town and the castle in Nosferatu were filmed on location...Murnau, however, making Nosferatu with a minimum of resourses saw all that nature had to offer in the way of fine images...Nature participates in the action."

Close-up magazine during 1929 reviewed the film, unaware that the Wisconsin Film Society would later favor the 1931 Tod Browning version, "The film opens with beautifully composed shots typical of Murnau (one spotlight on the hair, now turn the face slightly, and another spotlight)....It is unquestionably a faithful transcription of the book.

During 1926, when Murnau was readying to come to American, the periodical Moving Picture World interviewed his assistant, Hermann Bing, "Murnau's intention is to try to make pictures which will please the American theatre patrons- commercial successes because of their artistry....Murnau's object will be not to describe but to depict the relentless march of realities not for the objective, but from a subjective viewpoint." This almost seems like a nod to Carl Th. Dreyer's later film "Vampyr", other than that Dreyer's film had been made during the advent of sound film while Murnau was in America, shortly before Murnau's death. Fox Film publicity happenned to announce F.W. Murnau's coming to America by withholding the title of his debut American fim, giving the name of the dramatist that wrote its photoplay as Dr. Karl Mayer. "Theater Audiences Everywhere Are Waiting For This Creation".

Silent Film

Silent Horror Film

< Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

Silent Film

Scott Lord Silent Film: Gosta Ekman in Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

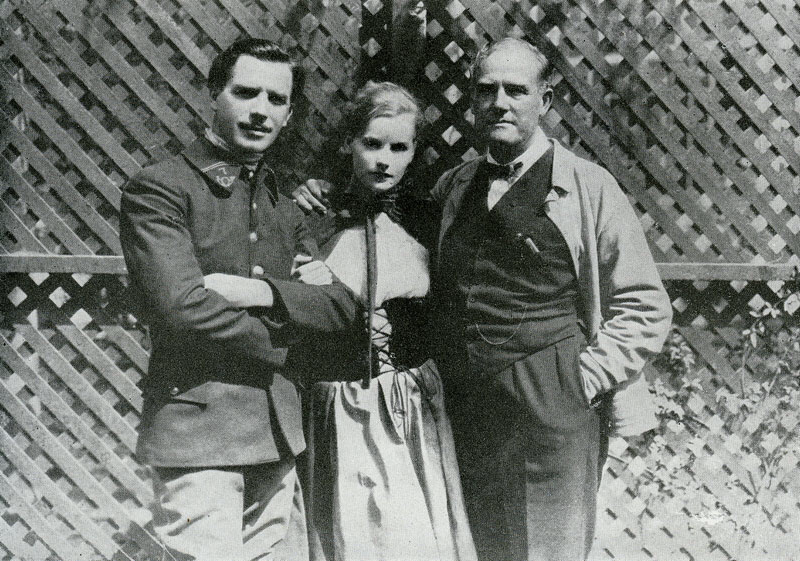

The immanent departure of director F.W. MUrnau for America had already been announced by the periodical Motion Picture News during late 1925 while Murnau was readying the film "Faust". It was to star Gosta Ekman, "a young Swedish actor who has the title role. He has been a star on the legitimate stage and is now making his first appearance in pictures."

Janet Bergstrom, University of California , writes that with the film "Faust", among others, Murnau had "unchained the camera" with moving shots that seemed unique...sweeping the audience's emotions with them". Of these moving shots, Bergstrom brings to our attention tracking shots that were photographed above their subject by having rails mounted on the ceiling of the studio.

The use of a mobile camera by Murnau is clearly referred to by Robert Herlth, a designer of sets on the film "Faust", who wrote on the lighting of the film in a chapter entitled "With Murnau on the Set" included in the volume Murnau, published by Lotte H. Eisner. The set designer quotes Murnau as having said, " 'Now how are we going to get the effect of the design? This is too light. Everything must be made much more shadowy.' And so all four of us set about to trying to cut the light...We used them (screens) to define space and create shadows on the wall and in the air. For Murnau, the lighting became part of the actual directing of the film.'" silent film Silent Horror Film Silent Horror

Greta Garbo written by

Scott Lord on Silent Film, Scott Lord on Mystery Film

at

6:23:00 PM

No comments:

Greta Garbo

F.W. Murnau,

Silent Film 1926

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)